'Women who smoke during pregnancy may be programming their children to become smokers as adolescents'

-Mums-to-be hand down addiction, Michelle Pountney, November 29, 2006, Herald Sun

http://www.news.com.au/heraldsun/story/0,21985,20837535-24331,00.html

As I was skimming The Sun this morning (and in general over the past few weeks), I was struck by 1) the amount of articles written about motherhood or pregnancy 2) the equally prescriptive nature of the articles particularly with regard to moral imperatives surrounding women's preconception/pregnant behaviours.

I will be the first to admit that even though I am wholeheartedly a feminist and adamantly support choice for women in every form, when I see a pregnant woman smoking I can't help but stare. I am not necessarily staring to be critical of her behaviour but perhaps more out of surprise; I think you have to be pretty courageous to smoke in public when you are pregnant considering the ridiculous level of surveillance women must negotiate when they are visibly pregnant. Beyond the disparaging looks imploring 'bad mother', it wouldn't surprise me if pregnant smokers are actually scolded by strangers for their culturally 'inappropriate' maternal behaviour.

The article in the paper today highlights perhaps relevant health information however it also highlights and instigates a more troubling representation of the fetus as person that is unequivocally in conflict with its mother. Moreover, the well-being of the fetus, particularly in anti-smoking campaigns during pregnancy, takes precedence as a public actor and holds a valuable position in the cultual imagination more so than the mother. For instance, as this article suggests, babies become 'programmed' for nicotine addiction in utero which is clearly dangerous. However, I find it interesting that this article (and many others like it) never suggest that a woman should stop smoking because the behaviour is consistently cited as being unhealthy not just for the fetus but for her. Smoking during pregnancy is considered as not only a personal failing on the part of the woman but also as a social problem:

'...mothers who smoked during pregnancy were younger and less likely to have finished secondary education, had lower family income, were more likely to be depressed, had poorer partner relationships and were more likely to consume alcohol during pregnancy'.

In this example, smoking is attributed to and vilifies young, lower-class mothers and makes no reference to middle-upper class who invariably smoke during pregnancy as well. In this sense, women who smoke are not only blamed for hurting their own babies, they bear the brunt of a social epidemic that results in teenage pregnancy and threatens 'healthy societies'.

Perhaps seemingly innocuous in this guise, I think the legitimation of pregnancy surveillance and fetal protection in popular media only fuels and perhaps strengthens the moral judgments placed on women's agency in reproduction and engenders a feeling of public protection for fetuses as vulnerable and in need of rescue. In framing pregnancy as a conflict between mother and fetus, the 'rules' of pregnancy are not only enforced by women themselves but by the government and in social, legal and medical policies. Where will it stop? Will women be banned from smoking during pregnancy? Will women be charged with 'fetal abuse' if they are caught? Currently, legislators in South Australia have banned smoking in cars where children under 16 years are present. Is this an enfringement of the rights of parents or is it a well-meaning measure by a government that cares?

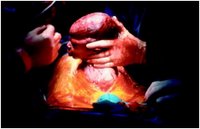

Now, dont get me wrong: If I were pregnant, I wouldn't smoke. I understand the risks and I wouldn't take a chance. However, it is this expanding recognition of the fetus as a person and in possession of rights that are in conflict with the rights of the mother that has me worried. In this example, it is not necessarily the smoking aspect which is of concern as much as how and why women's choices are being circumscribed. As the image above demonstrates, the glowing fetus is the only relevant actor and is entitled to a smoke-free womb as juxtaposed against the dark, shadowy figure of the irresponsible mother. Is smoking a reliable indicator of a woman's commitment to her pregnancy and by extension, her baby?

For more information on this debate, consult the work of feminist scholar Laury Oaks, in particular 'Smoke-Filled Wombs and Fragile Fetuses: The Social Politics of Fetal Representation', Signs, 26(1), 2000, 63-108 or her book Smoking and Pregnancy: The Politics of Fetal Protection (Rutgers University Press, 1999).